In, out, up, down, on, off. Everyone knows words like these can be prepositions. But did you know these words can sometimes function as adverbs instead? How can you tell the difference? And what about phrasal verbs like “turn off” or expressions like “push down”?

This last question came up at Ellii when a customer mentioned that in the phrase “push the switch down,” “down” is an adverb, not a preposition.

Let’s review the basic rules, discuss the trickier cases, and decide if it’s worth teaching the difference between prepositions and adverbs to our students.

What is a preposition?

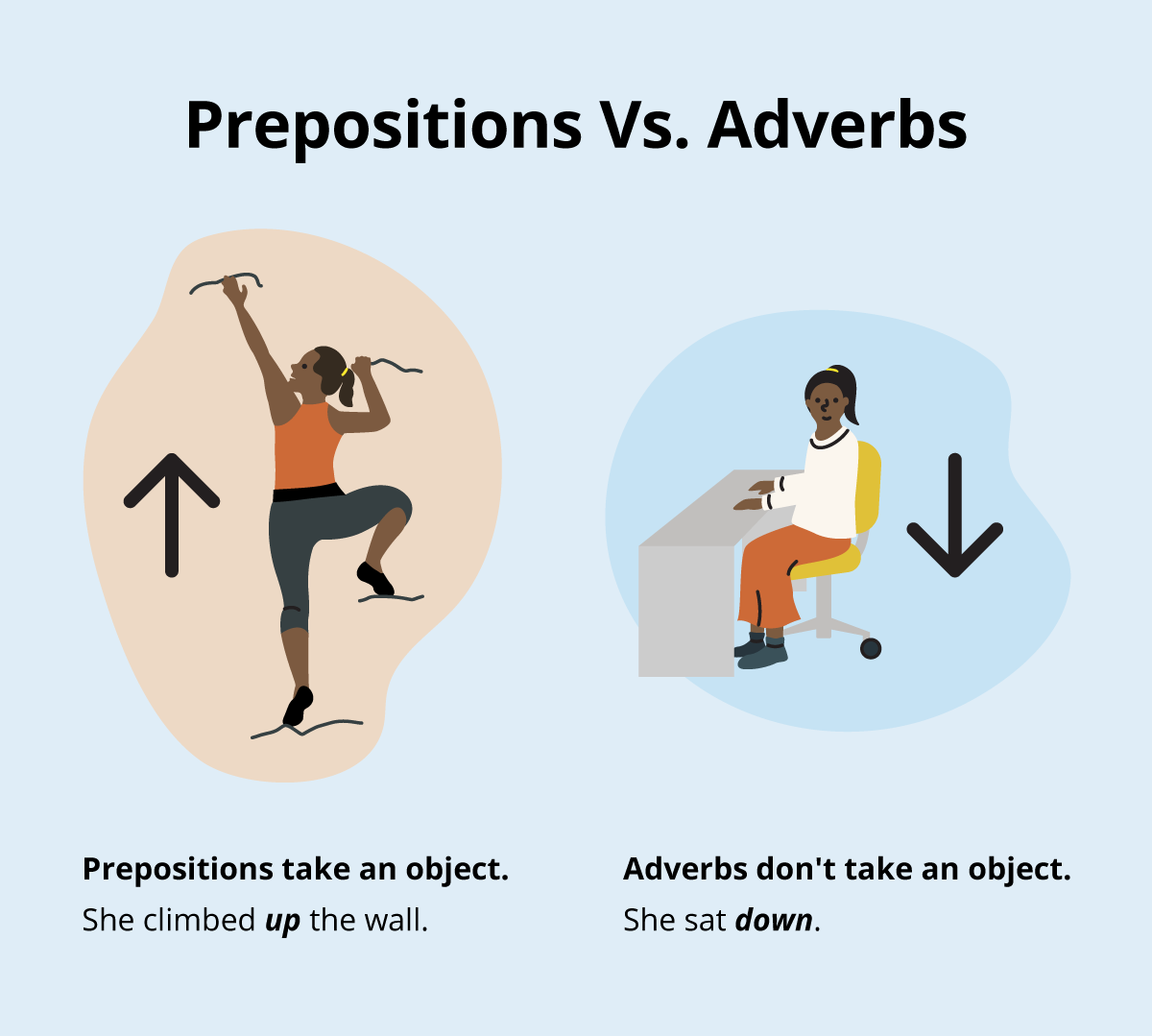

A preposition takes an object. If there’s a noun following the term, it usually indicates the term is a preposition, not an adverb.

Of course, not all prepositions are so straightforward, which is why it’s also important to learn about the trickier cases before teaching them to your students (should you so choose).

Examples of prepositions

- He ran down the stairs.

- Maria looked out the window.

- They talked in circles and couldn’t reach a decision.

Try our Prepositions lesson for practice.

What is an adverb?

An adverb doesn’t take an object. Adverbs such as these usually appear at the end of the clause or sentence.

Keep in mind that not all adverbs are created equal and that there are a few exceptions to be aware of.

Examples of adverbs

- She sat down.

- We’re going out at 7:00 pm tonight.

- When you arrive at the hotel, make sure you check in.

For general adverb practice, try our Adverbs of Manner lesson.

Tricky cases: Is it a preposition or an adverb?

When it comes to teaching about prepositions and adverbs, it's also important to be aware of the trickier cases.

What happens when a word appears to have an object, and therefore looks like a preposition, but is actually functioning as an adverb?

Tricky cases like this include phrasal verbs.

Phrasal verbs are two or more words (usually a verb and a preposition) that work together to create a new word with a completely different meaning from the original words.

call (verb) = to dial someone’s phone number

off (preposition) = from a place or position

call off (phrasal verb) = to cancel

When it comes to phrasal verbs, the adverb is defining or describing the verb, not the object.

Examples of phrasal verbs

- He looked up her number. (up = adverb)

- The class president called off the meeting. (off = adverb)

- You should check the schedule out. (out = adverb)

How to determine if the term before an object is an adverb

According to the Chicago Manual of Style, a good test for determining whether the term before an object is an adverb is to detach the term + object and see if it makes sense.

They give this example: “I looked up his biography.” Detaching “up his biography” doesn’t make sense, and therefore “up” is an adverb in this case.

How to decipher other tricky verb expressions

What about other verb expressions (also called collocations) like “push down” (that our customer asked about earlier)?

You can say “push down the switch” or “push the switch down.” Is “down” defining the verb “push,” or is it part of the prepositional phrase “down the switch”?

Does Chicago’s test help us here?

Is “down the stairs” in the sentence “He ran down the stairs,” which is clearly a preposition, similar to “down the switch” in the sentence “He pushed down the switch,” and therefore also a preposition?

We can turn to Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary for help with these expressions.

Under the adverb entry for “down,” they give the following examples:

- They set the cake down on the table.

- Lay down your book for a minute.

Clearly, Merriam-Webster classifies the terms in these types of verb expressions as adverbs, not prepositions.

I must admit, I’m still a bit puzzled by cases like this. Can we say the rule is that if you’re able to move the object, it’s always an adverb (as in turn on the light / turn the light on)? Do you agree that the previous two bullet examples are adverbs, not prepositions?

I’ll accept it, but I’m not 100% convinced. I don’t see a whole lot of difference between “go down the stairs” (preposition) and “lay down your book” (adverb).

Should we teach this to our students?

In my experience, most textbooks don’t get into the difference in parts of speech for words like "down," "on," "off," etc. The many textbooks that I’ve seen during my teaching career simply call these terms prepositions.

I believe that, in general, students are capable of learning and understanding the sentence positions and meanings while grouping these words under the “preposition” umbrella.

This could be a discussion you could have with higher-level students, but for lower-level students, it would only create unnecessary chaos and confusion.

What do you think?

Should we be teaching the difference between prepositions and adverbs to our English language learners? Why or why not? I’d love to hear your thoughts on this!

Sources

- The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, section 5.180.

- Collins Cobuild English Grammar, section 6.82–6.87.

- Merriam‑Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th edition, entries such as “down.”

Editor's note: This post was originally published in May 2013 and has been updated for comprehensiveness.